By Ian Hartwell, Senior Scientist for Aquatic Toxicology, NOAA National Status and Trends Program.

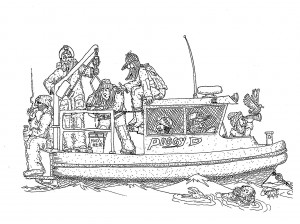

The first day in Elson lagoon was very productive. We were able to sample six sites. This was important because the sampling locations are spread out and travel time between them and the inlets eats a lot of time. Also, the Beaufort coastline is shallower than the Chukchi side, so the ship lies further offshore and our transit time is even longer. Elson Lagoon and Dease Inlet are separated from the open Arctic Ocean by a series of barrier islands known as the Plover Islands. There are several gaps between the islands, but passage between them is treacherous with shoals and uncharted obstructions. The charts data are 40-50 years old, so nothing on them is 100% reliable. Channels have migrated and shoals have developed and our navigation is governed by watching the depth sounder to see how closely it matches what is on the electronic charts. If we run aground, we will be stranded, as the ship’s emergency rescue boat is an open zodiac designed for quick response to a man overboard situation with no need for navigation or radar capability. Finding us behind the islands in the fog would prove to be impossible. Entering Elson Lagoon in the north, getting all six sites, and exiting through a pass in the middle of the lagoon will allow us to use Sanigaruak Pass further east the next day, greatly reducing our travel time. The North Slope Borough Wildlife Dept. has told us we should be able to get through with our boat.

The next day started well enough, but the wind was predicted to rise out of the northeast. Sanigaruak Pass is shallower than we expected, and the channel has shifted to the west. We drive deep into the bay to our farthest targeted sites, but the weather is deteriorating. It is decided to go by one last station on the way out because it is on the way to the pass, but by the time we get there, the wind is starting to howl, so we simply make a run for it. Even behind the barrier islands, the waves are making progress difficult. Outside the islands we had to cross miles of open ocean in 4-5′ choppy swells to reach the ship. Every third wave was over the bow. It took us two exhausting hours to get to the safety of the ship.

Next we will rest a short time while the science party from PMEL runs one of their transects out to the edge of the continental shelf. But progress was very slow. The persistent northeast wind is pushing the sea ice into our path. It is no longer a novelty. The ship weaves around the ice bergs that are no longer just a few feet across, they are approaching the size of the ship. Some are monolithic blocks, some are jumbles of chunks that were jammed together in old pressure ridges, some have promontories sticking up at odd angles. As night falls the ice field looms up on the radar screens. It takes all night to run the transect. In the end, we sit two miles short of the last station, close to a solid field of ice bergs with the wind pushing it slowly toward us, but we cannot move into it. The bridge is not a happy place.

We retreat to the next line that the PMEL crew wants to sample, but the wind continues out of the northeast, up to 20 knots. Blowing wind over the ice generates a dense fog but the ice keeps the waves from building too much. Eventually, all work stops and we have to wait for the wind to shift or lay down. The weather reports from NOAA and the Navy are directly contradictory, so we have to just wait and see what happens next.

By Sunday, we finally got a reprieve. We were able to get in a half day on the water in Smith Bay on Sunday and Monday, and sampled most of what we needed there. Harrison Bay is a complete write-off, however. We will not get there, and PMEL will not get to run their final transects. So, we must run back to Barrow to offload. PMEL still has work do there, but weather is expected to be so bad by mid-week, we may not be able to go ashore. So we spend all night packing samples and gear into the wee hours. The gear will be offloaded at Dutch Harbor, but the all-important samples have to be shipped as soon as we get ashore. There is a temporary dock at Barrow, but it has been pulled out of the water for the anticipated weather so we have to beach the boat, and pass the frozen sample coolers hand over hand to shore. Finally, we are able to get them shipped on a cargo flight to Anchorage. By evening, our passenger flight gets canceled due to fog, so we have no place to go, and no way to get there. Sort of like sitting in an ice field. So we wait, still amazed with what we were able to accomplish over the last month.

About this mission:

During August, the State of Alaska Department ofEnvironmental Conservation, NOAA National Status andTrends Program, and the University of Alaska Fairbanks Schoolof Fisheries and Ocean Sciences will be sampling estuaries andbays along the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. We are planning tostudy sediments, water, and invertebrates (animals that livein the ocean sediments) to learn more about the naturalconditions of these regions. Minimal samples will be collected, and every effort to reduce our impacts will be made.

For more information, contact Ian.Hartwell@noaa.gov.