Mesophotic and deep benthic communities were injured across a large area in the Gulf of Mexico by the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in 2010. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and partners are leading a long-term project to inform coral restoration in areas impacted by the spill. The “Coral Propagation Technique Development” project aims to develop methods and techniques for effective enhancement of coral recruitment (or settlement of coral larvae) and growth that can eventually be implemented at a large scale for restoration.

The most direct way to restore coral aggregations is to facilitate new growth of coral species that were impacted by the oil spill. Restoring these coral species requires new understanding of their biology, genetics, ecology, and health; and development of new techniques to grow and propagate the corals. Scientists at NOAA and USGS are seeking new and effective ways to grow, propagate, and transplant mesophotic corals.

During expeditions in 2022 in the northern Gulf of Mexico, researchers surveyed the seafloor in the lower mesophotic zone (50-100 meters) and used a remotely operated vehicle to collect healthy mesophotic coral samples for laboratory-based studies. A CTD rosette was cast at each site of coral collection, allowing scientists to collect water samples and environmental data to help them replicate the same environment in the laboratory.

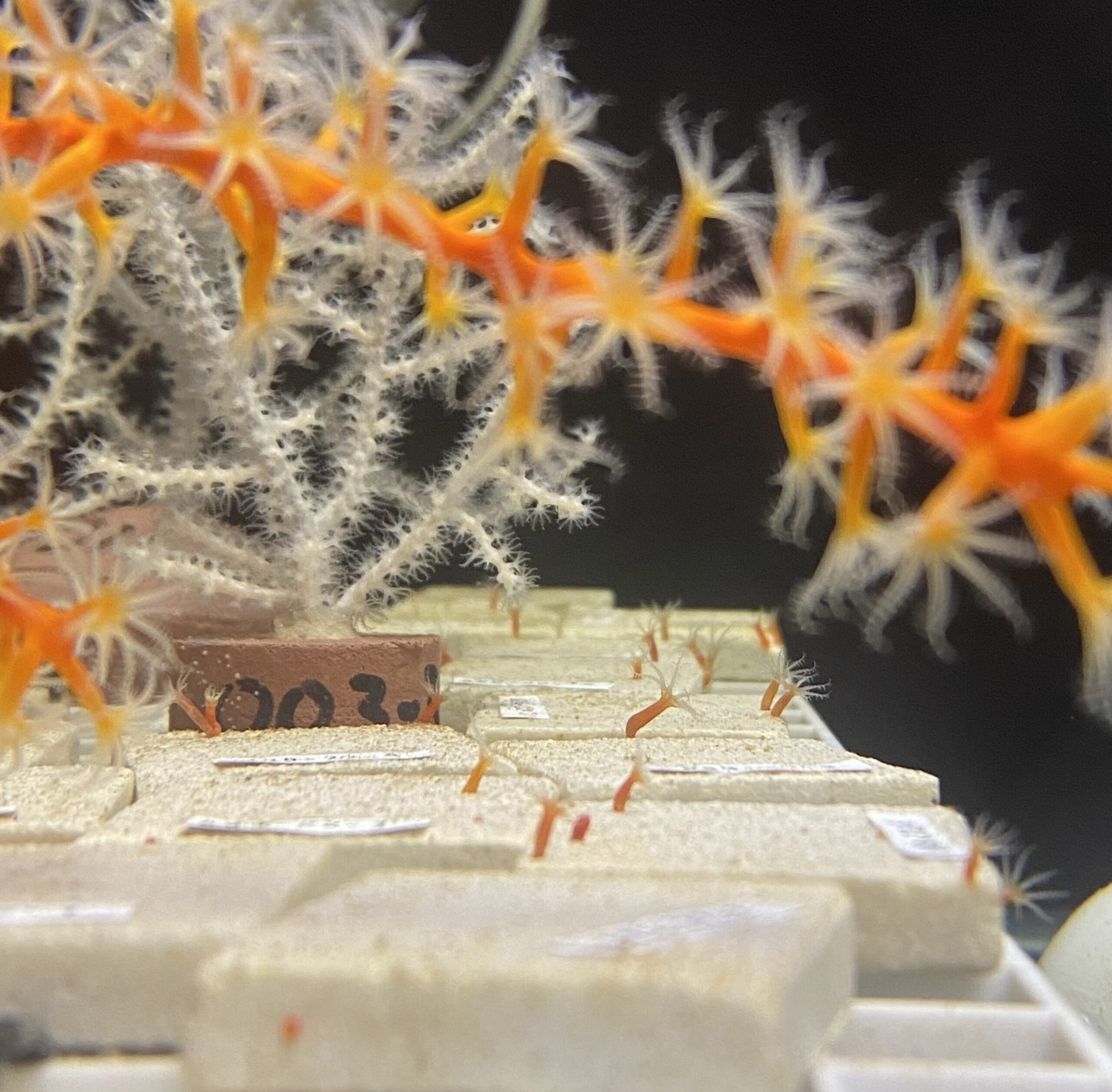

Three species known to be substantially impacted by the DWH spill were collected – the gorgonian corals Swiftia exserta, Muricea pendula, and Thesea nivea. Gorgonian corals are soft, branching corals made up of small, individual polyps. Live coral samples were transferred to three federal labs: NCCOS’ Hollings Marine Laboratory (HML), Southeast Fisheries Science Center’s Galveston Laboratory, and USGS Wetland and Aquatic Research Center in Gainesville.

To house and maintain the live corals in a laboratory setting, the three teams have each designed and installed insulated cold-water tanks at their respective facilities. Cooler water temperatures are necessary due to the depths at which these corals are found. The teams are actively experimenting with coral husbandry techniques. This includes testing different environmental conditions, including light availability and water flow, to assess the impacts to the coral specimens; and assessing the amount of food needed by the corals to remain healthy.

|

The coral propagation lab at the USGS Wetland and Aquatic Research Center. Credit: USGS |

|

Aquatic system at Hollings Marine Lab in Charleston, SC specially designed to support mesophotic and deep-sea corals. Credit: NOAA |

Due to low levels of natural light at mesophotic depths, conventional wisdom says mesophotic corals rely on surface plankton falling to the seafloor as a food source, unlike their shallow water counterparts who rely on photosynthesis. This results in larger nutritional requirements for mesophotic corals, which are difficult to manage in laboratory enclosed systems. The aquaria teams must find a balance between providing the corals with plenty of food while maintaining water chemistry and quality. These requirements are demanding – each coral branch is hand fed between two and six times a day.

To help contribute to the baseline understanding of these coral species and their needs, the USGS team in Gainesville is investigating how different substrate types may enhance coral growth and coral larvae recruitment, and implementing various treatments for stressed and diseased corals to help identify successful treatment regimens. Future work will focus on discrete experiments on mesophotic corals to answer questions concerning the corals’ potential for photosynthetic activity, identifying food resources used by the mesophotic species, and determining the role that light may play in their feeding behavior and cycles of reproduction.

In Charleston, NCCOS scientists are experimenting with fragmentation, a process of cutting the corals into smaller pieces to allow for asexual reproduction. In addition to creating more corals, this technique allows scientists to study coral survivorship and growth rates. The corals can also reproduce sexually, but in order to fully understand coral reproductive modes and processes, scientists need to look more closely at individual coral polyps and their reproductive contents. The scientists at HML have outfitted a histology lab to do just that. Using a microtome, researchers are able to thinly slice coral tissues so they can be mounted on slides and examined under a compound microscope. The new capacity for histology at HML allows scientists to determine the gender of the corals, their modes of reproduction, and how advanced they are in their reproductive cycle.

Coral spawning was observed in Galveston and Gainesville, and several hundred new baby corals that were reared in captivity are currently growing in the tanks. In Galveston, experimentation will soon take place to learn more about mesophotic coral biology, and how to maximize growth and survivorship for out-planting and several other types of restoration strategies. Best practices and standard operating procedures are being developed for scaling propagation to reach the goal of restoring injured communities.

This effort is part of a collaborative set of projects with the overarching goal to improve our understanding, inform management, increase public awareness, and ensure resiliency of mesophotic and deep-benthic communities.