In the first major study of the harmful algal bloom species Alexandrium catenella in Cook Inlet, Alaska, NOAA scientists found a link between ocean temperature and bloom development. Alexandrium species produce a neurotoxin responsible for paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP), which happens after consuming shellfish with accumulated toxin. PSP poses a serious health threat in Alaska and prevents effective use of shellfish resources.

Though PSP toxins in Alaskan shellfish are well characterized, little is known about the environmental conditions that foster toxic A. catenella blooms. To address this question, scientists collected water samples and environmental monitoring data along Lower Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay over a five-year period between 2012 and 2017. During the course of the study, the northern Pacific underwent a warming event that caused average winter minimum and summertime maximum water temperatures to increase by more than 2°C. These elevated water temperatures promoted greater development of A. catenella blooms in Kachemak Bay, causing shellfish collected in the latter portion of the study to become toxic.

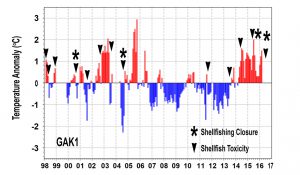

Further analysis of monthly surface water temperatures showed that other periods of anomalously warm conditions occurred repeatedly between 1998 and 2016, following many of which shellfish toxicities exceeded the FDA action level (80 micrograms of toxin per 100 grams of edible shellfish tissue). During periods with cold anomalies, shellfish toxicity was generally low. The analysis indicated that regional water temperature data may be used as an early indicator of A. catenella bloom formation and PSP risk in the region, and potentially, across the state.

The findings have serious implications for coastal regions of the arctic and subarctic where Alexandrium blooms are normally suppressed by cold water temperatures. Recent rising ocean temperatures in the Bering and Chukchi Seas have resulted in record low winter sea ice and may promote Alexandrium blooms, resulting in accumulation of PSP toxins in marine mammals and seabirds, and increased risk to human populations dependent on these resources.

For more information, contact Mark.W.Vandersea@noaa.gov.