An NCCOS-funded study found that shoreline armoring in Chesapeake Bay promotes the spread of the invasive common reed (Phragmites australis) by stimulating greater genetic diversity in the plant, which allows it to become reproductively viable sooner than it would in an undisturbed environment.

Phragmites australis has spread throughout most of the U.S., especially in freshwater and brackish estuaries with hardened shorelines. Armoring shorelines with hardened structures, such as seawalls and riprap revetments, to prevent erosion and protect property is common practice around the world. Pressure for more shoreline hardening is expected to increase with predicted sea-level rise and increased storm frequency associated with climate change, despite the potential negative effects such hardening could have on nearshore ecosystems and native species.

An earlier NCCOS-sponsored study found that invasive Phragmites australis in Chesapeake Bay thrives around altered and hardened shorelines and disturbed marshes and beaches. Building on these results, the new study tested the ideas that shoreline erosion structures are associated with seedling recruitment, resulting in higher levels of genetic diversity.

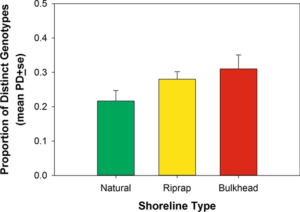

The researchers used a technique known as microsatellite analysis to examine the genetic diversity of P. australis stands associated with bulkhead- and riprap-armored shorelines and compare it to P. australis stands from natural shorelines. The team found that shoreline hardening promoted the establishment of multiple genotypes in P. australis stands (Figure 1), which effectively decreased the time from initial establishment until viable seeds are produced, thereby fueling additional spread. Because P. australis seed viability depends on cross-pollination, higher levels of genetic diversity in stands associated with hardened shorelines are more likely to contribute to the spread of invasive P. australis.

The potential importance of shoreline structures in the establishment of genetically diverse stands adds to what the project team previously found for wetland stands that were not associated with shoreline structures. The researchers concluded that the extent of shoreline modifications in Chesapeake Bay has contributed to the spread of P. australis by seeds.

The results have implications for both the management of P. australis associated with existing shoreline structures and decisions about future shoreline structures. The researchers note that expansion of P. australis is just one consequence of shoreline hardening, which can also result in higher methane emissions, loss of seagrass, and changes to the compositions of fish and waterbird communities.

The study was part of a larger NCCOS project investigating the Influence of Shoreline Changes on Chesapeake and Delmarva Bay Ecosystems.