No-take marine reserves are critical tools for protecting reef fishes and should include all habitats the fishes use. However, we have little information about reef fish foraging in seagrass beds. To improve reserve design, we will work with a range of species in the Florida Keys to understand where reef fish forage and how this is affected by current and future configurations of seagrass beds to aid better protection of species using multiple habitats.

Why We Care

Tropical marine ecosystems consist of a wide range of connected habitats, with the major components being coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves. Each of these habitats is biodiverse and supports critical ecosystem services (i.e., benefits that humans receive from the environment). For example, reefs provide storm defenses, food, and tourism opportunities, while seagrass binds sediment, sequesters carbon, and absorbs nutrients. Because of the threats to these habitats (e.g., climate change, declining water quality, overfishing, and disease) extensive conservation efforts have been undertaken to protect their ecosystem services. Marine protected areas (MPAs), containing no-take reserve zones that ban fishing, are one of the most common tools used to protect significant natural and cultural resources for the benefit of present and future generations.

One of the key design principles for MPAs and no-take zones is ensuring the inclusion of all habitat types to maximize the chances of protecting the most species and capturing links among these habitats, such as when fishes move among habitats to forage. For example, grunts aggregate on reefs during the day and then migrate into seagrass beds at night to feed. Given the importance of seagrass foraging habitats, it is vital that they are incorporated into the design of MPAs and no-take zones. However, globally, seagrasses are poorly represented in current MPAs and fish movement is often not adequately addressed in MPA design.

In the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, no-take zones, known as Sanctuary Preservation Areas, are explicitly designed to protect fish populations, yet they contain only a small area of seagrass (< 4 km2 across 22 Sanctuary Preservation Areas containing > 8 km2 of reef and hard bottom habitat). At present, we have a limited understanding of how much seagrass is needed and how this varies with seagrass quality (e.g., prey availability) and configuration (e.g., distance from reefs). Furthermore, it is important to know how foraging patterns will change in the future if seagrass beds become healthier or further degrade. Given the importance of reef–seagrass connectivity, we will determine how much seagrass is necessary to support foraging for different types of reef fishes, as well as identify how much seagrass is required based on habitat configuration and how this might change over time. This information will provide managers with the tools to better protect seagrass habitat within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and determine if Sanctuary Preservation Areas need to be reconfigured to be more inclusive of seagrass beds.

What We Are Doing

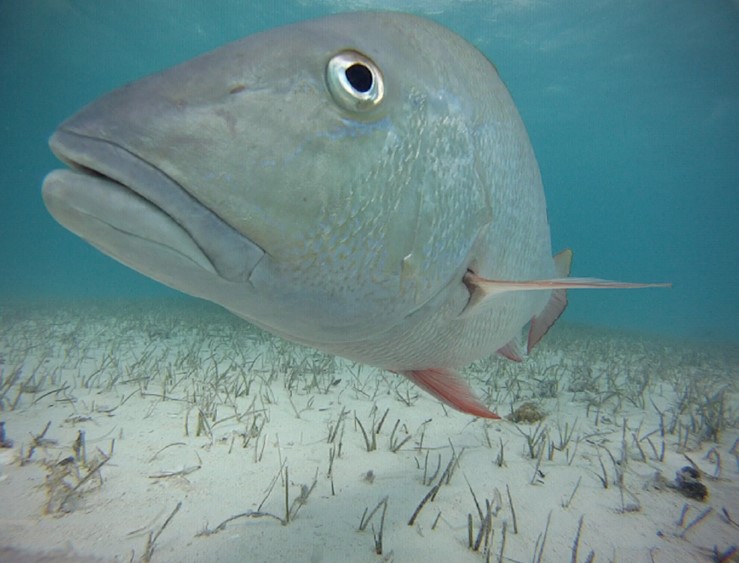

The FISHSCAPE Project (Fish In Seagrass Habitats: Seascape Connectivity Across Protected Ecosystems) is studying four model fish species, each with differing foraging modes, to determine how they use the seagrass beds of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The species are: white grunt (Haemulon plumierii), yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus), mutton snapper (Lutjanus analis), and great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda). The foraging (seagrass use) movements of the four species will be tracked by acoustic telemetry and related to prey availability and accessibility, the energetic costs of this foraging will be measured in aquaria, and stable isotope analyses will examine the reliance of these fishes on seagrass food sources. All information will be integrated with species-specific bioenergetic models that will estimate the amount of seagrass needed to support foraging in any seascape configuration throughout the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. We will also use a long-term seagrass monitoring dataset to examine how seagrass habitats change over time and how this might affect their use by fishes.

To ensure that our project and its outputs are useful to managers, we will work closely with resource managers to translate our results. This study will produce a user-friendly online tool that allows managers to estimate, for anywhere in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, the seagrass area needed within a new or expanded Sanctuary Preservation Area to support foraging reef fishes under current and future habitat states.

This work is part of the Regional Ecosystem Research Program’s Federal Funding Opportunity focused on understanding species’ habitat usage and connectivity. The project is funded by NCCOS and is conducted in collaboration with the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries and the National Marine Protected Areas Center. Alastair Harborne with Florida International University (FIU) is the project’s principal investigator.