A study supported by NCCOS has found that the dominant type of beach grass influences the shape of coastal sand dunes, which in turn influences how well those dunes protect our coasts from flooding.

Over the last decade, there has been growing recognition that coastal edge habitats, such as dunes, provide important protection from the threats of extreme storms and chronic sea level rise. In the study, scientists from Oregon State University, the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, show a relationship between different types of dune grass and dune shape along 320-kilometers of the Outer Banks from Virginia to North Carolina.

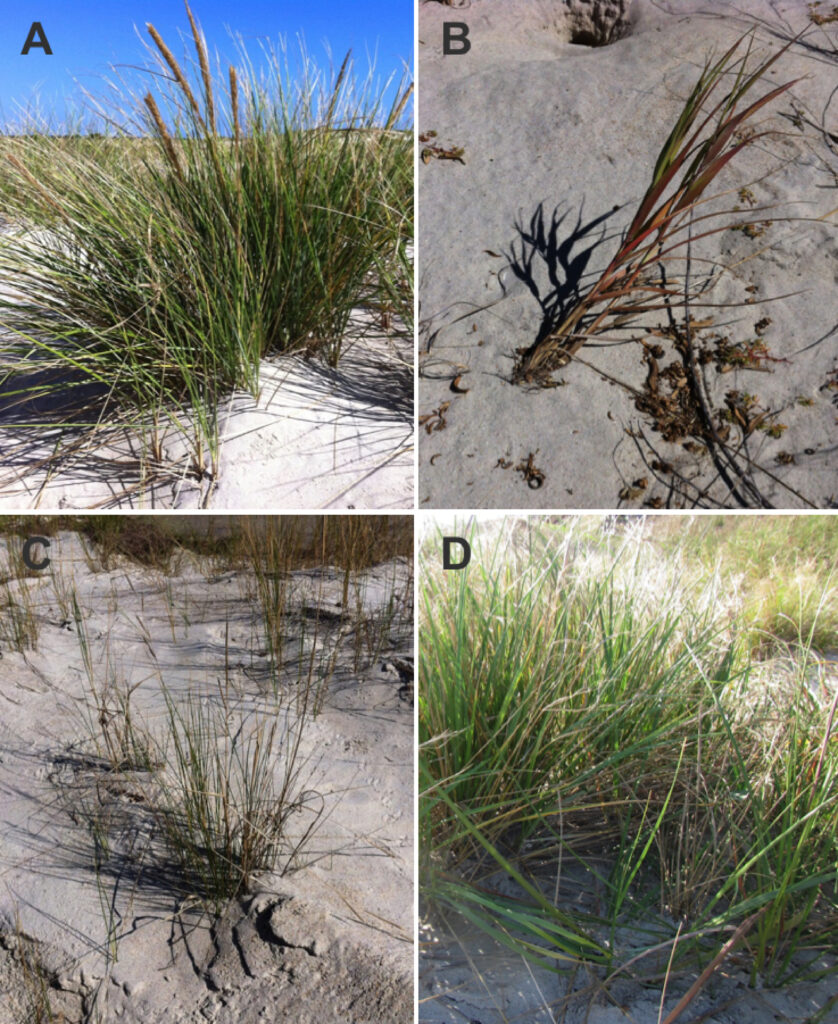

cordgrass), and (D) Uniola paniculata (sea oats) in foredunes of the Outer Banks islands from Virginia to North Carolina, USA. Photos by S. D. Hacker, OSU.

Coastal dunes arise from feedbacks between vegetation and sand supply. Four dune grasses along the Outer Banks in North Carolina, varied significantly in their functional morphology (i.e., relationships between the structure of an organism and the function of the various parts of an organism). In other words, how the structure of the plant above the sand and below the sand (i.e., roots), affect how sand accretes (i.e., gathers together) around the plant to change the dune shape.

The study sought to determine the ways in which the four most common and co-occurring dune grass species, i.e., Ammophila breviligulata (American beachgrass), Panicum amarum (bitter panicum), Spartina patens (saltmeadow cordgrass), and Uniola paniculata (sea oats) differ in their functional morphology for sand accretion (see images). The investigators surveyed the distribution of plants, shape and size of plants, and associated change in sand elevation of the four plants along the profile line. On the foredunes, where all four grasses were present, the different types varied in their abundance. Sea oats and American beachgrass were both dominant at the foredune toe/face and sea oats were dominant at the foredune crest. Saltmeadow cordgrass was most abundant at the foredune back/heel, where it was also dominant with sea oats. Bitter panicum had relatively low abundance across the profile.

Results showed that American beachgrass had dense and clumped shoots (image A), which allows for greater sand accretion. Coupled with a fast outward spread, it tends to build tall and wide foredunes. Sea oats (image D) had fewer but taller shoots and showed about 42 percent lower sand accretion. Coupled with slow outward spread, it tends to build steeper and narrower dunes. Bitter panicum (image B) had similar dense and clumped shoots, and had a similar sand accretion rate to sea oats, despite bitter panicum’s shorter shoots, suggesting that how clumped the shoots are in an area is more important than shoot height. Saltmeadow cordgrass (image C) accreted sand the least and did not always cause an elevation change, though is still considered a dune builder.

This has future implications – American beachgrass cannot live further south than Cape Fear, NC, since the grasses cannot live in temperatures higher than 35 °C (95 °F). If temperatures over 35 °C move north past Cape Fear, the species will no longer dominate in those regions. Under the notion that taller and wider fore dunes have better coastal protection properties, a loss of American beachgrass dominance could make for more vulnerable coastlines in those areas.

For details regarding the study, see Hacker, Sally D., Katya R. Jay, Nicholas Cohn, Evan B. Goldstein, Paige A. Hovenga, Michael Itzkin, Laura J. Moore, Rebecca S. Mostow, Elsemarie V. Mullins, and Peter Ruggiero. 2019. Species-Specific Functional Morphology of Four US Atlantic Coast Dune Grasses: Biogeographic Implications for Dune Shape and Coastal Protection. Diversity 11 (5), 82; https://doi.org/10.3390/d11050082

This study was supported in part by the NCCOS Ecological Effects of Sea Level Rise (EESLR) project “The Coastal Recovery from Storms Tool (CReST): A Model for Assessing the Impact of Sea Level Rise on Natural and Managed Beaches and Dunes.” The project is led by Professor Peter Ruggiero of Oregon State University.

For more information, contact David Kidwell.