Coastal dunes and wetlands provide many benefits — protection against storm surge and flooding, critical habitat for wildlife, and recreation opportunities for outdoor enthusiasts — yet they have been greatly degraded over the last century. Habitat restoration is often a costly endeavor that can lead coastal communities to question whether the investment is “worth it.” Two NCCOS-supported studies looked at public valuation of two types of restoration in the Pacific Northwest to determine what the public thinks is worth doing.

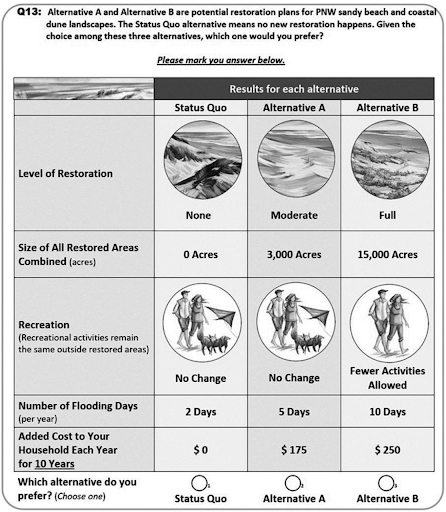

The most recent of the two studies asked respondents to choose between different types of potential dune restoration projects that varied in project size, restoration quality (how close to the dune’s natural state), recreation access, flood risk, and cost. Researchers found that the largest economic gains would come from projects that favored restoring dunes closer to their natural state rather than projects that only focused on protecting large areas. The public also preferred projects that allowed access to recreation but were willing to pay for projects that restricted access, as long as those projects focused on returning dunes to their natural state. In short, the public preferred restoration quality over quantity.

The previous study from the same project also looked at the return on investment of protecting coastal wetlands that serve as nursery for young salmon. Researchers combined survey data with a statistical model to estimate the economic value of increasing the spawning population of Oregon Coast Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch).

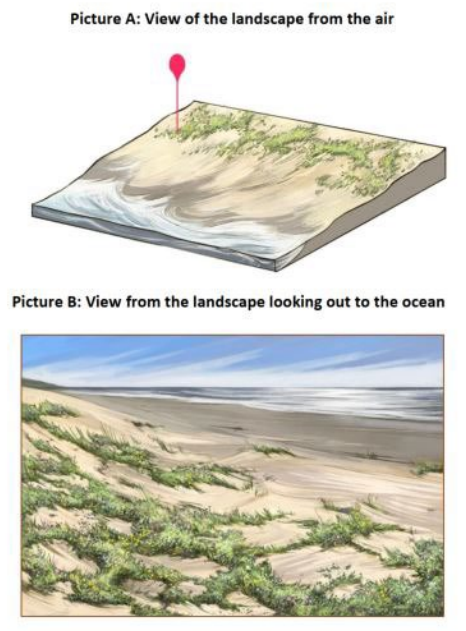

Picture A shows a view of a section of the landscape from the air and to the side. Picture B shows the view when a person stands at the location of the red flag in picture A and looks towards the ocean.

This approach allowed conservation managers to estimate the economic benefits of any restoration action for Oregon Coast Coho habitat. Testing this method for a small Oregon estuary, the team found that management efforts that led to an immediate increase in salmon numbers generated over $63 million in economic value to the Pacific Northwest, a much greater benefit then when the same salmon numbers were reached through gradual population increases.

These studies were supported by the NCCOS-funded project A Multidisciplinary, Integrative Approach to Valuing Ecosystem Services from Natural Infrastructure led by Oregon State University. Project partners include the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, and Oregon Sea Grant.

Citations: